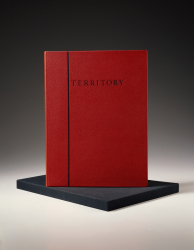

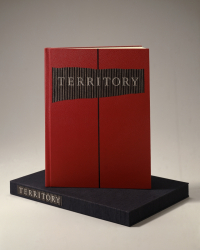

Twenty-one poems by Mary Julia Klimenko; one original drawing and five photolithographs of drawings by Manuel Neri. Introduction by Frances Mayes. The book was completed in 1993; designed and published by Brighton Press, San Diego. Edition 55.

Introduction to TerritoryFrances Mayes’ Introduction to Mary Julia Klimenko’s book of poetry, Territory, published by Brighton Press, San Diego in 1993

The passionate and visceral poems of Mary Julia Klimenko’s recent She Said: I Tell You It Doesn’t Hurt Me contained many startling moments. The voice in most of the poems is that of Freida Kahlo writing letters to Diego Rivera, writing out of humid sexuality, her impending sense of death, the fiercely entwined love and dependence, these two suffered and gloried in. The poems go beyond the love story to a privately lyrical voice:

It is four in the morning. At this hour

Bones of children in the graveyard become flutes

For the devil. Even the wind is afraid …

And to the meditative voice of the artist:

A color changes

Like a lizard pursued. What color is a deer with

arrows stuck in its body? Does the color change

with pain and does it really matter?

…can you paint the color of a woman who listens

to crickets? Can you find a color for the pain

that travels miles through still night air . …

Territory, the new work, retains the immediacy and hunger of the Kahlo Rivera poems. The bedrock of that group is the grappling, always of the “I” and the “other.” Territory also stands on primary material.

Klimenko has three intense professions: poet (the seeker, the singer, the loner), therapist (the healer, the voyeur, the clairvoyant), the artist’s model, the object, the angel of transformation, the giver). These archetypal positions offer fertile and tense vantage points, as in the powerful “Seated Plaster Figure,” where she confronts her own conception of the figure, versus the artist’s preoccupations. In “You Alone,” she speaks directly to the recurrent “other”:

I am your music

I am the words through which you pass to get to the lake

The lake accepts us totally and there we commit

All the acts of humans

Cumulatively, what emerges in the poems is a sense of the essential female articulating from the dark regions areas still unexplored, unadmitted. The woman who makes love to a stranger in the tall grass, the woman who imagines leaving every day, the woman who in winter loosens her reputation and becomes a fool for breeding and especially the woman “no longer on the alert for evidence controlled/By other persons.” I am a brazen woman,” and “I am green sea foam” appear in the same poem. Others land time and again on this arachetypal female territory, Eve’s territory”:

…and yet I long to touch

To push into the soft grey flesh of it and warm

Us both inside where we never thought to feel.

from “My Mind is Like someone Else’s Lace

Intricate and Unfamiliar”

And what I love are hands underneath me, snow, featherbeds,

And the illusion that the devil is watching from shadow –

That pleasure cannot be eliminated completely, no matter how hard I pray.

from “Leering”

Truth and beauty. Keats said, that’s it, all we need. Reading Klimenko’s truthful and intricate poems makes me aware of how rarely the two actually come together. Complex truth, not over-easy truth, down to the bone beauty, not surface beauty. Manuel Neri’s work, too, always strikes me hard with just that combination. The poet John Logan said, “It’s not the skeleton in the closet we are afraid of, it’s the god.” Poetry and art this unafraid get us all closer to that god.

Frances Mayes, 1993